|

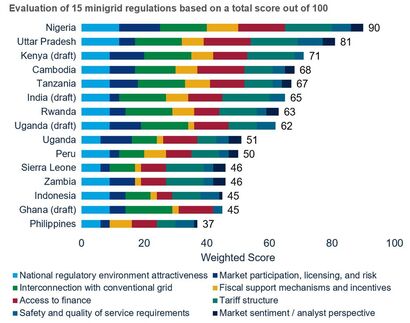

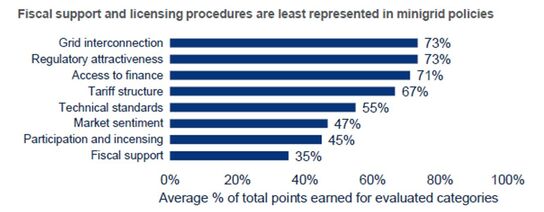

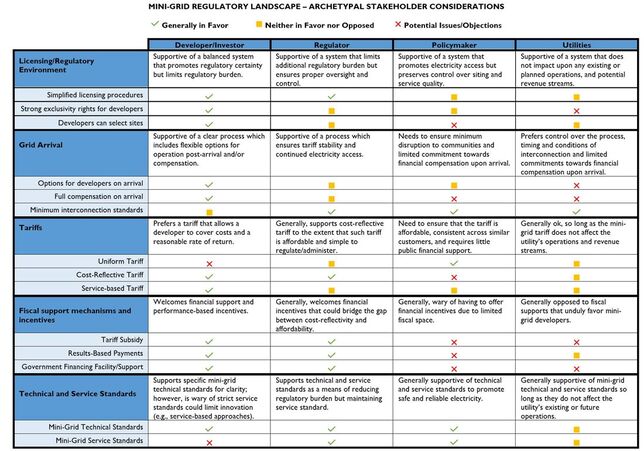

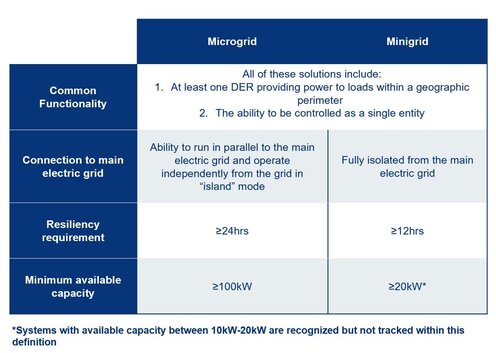

Minigrids have yet to scale on a trajectory reflective of their massive potential. BENJAMIN ATTIA, EMILY CHESSIN, AND ARTIE ABAL | OCTOBER 26, 2020 The energy access minigrid sector is simultaneously a nascent market and a cleaner reprise of a familiar technology set’s debut role as the original building block of the modern grid, targeted at underserved populations. This duality positions the sector as a fundamental piece of the integrated electrification puzzle. But despite consistent business-model innovation, steep cost learning rates and a rapidly diversifying competitive landscape, minigrids are still largely stuck in the “missing middle” and have yet to scale on a trajectory reflective of their massive potential. Recent estimates from the Minigrids Partnership suggest that minigrids could serve 111 million households (approximately 550 million to 600 million people) in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and island nations by 2030, but the World Bank's Energy Sector Management Assistance Program estimates there are currently only about 47 million people connected to minigrids (under a very inclusive definition of minigrid system architectures). The African Minigrid Developers Association reports that its members serve about 250,000 people. Insufficient policy environments are a well-documented bottleneck to the growth of the minigrid sector. Bad or nonexistent targeted policy shuts out even risk-hungry private investors, sends developers packing to greener pastures or offloads undue risks or costs to customers. For instance, unclear project approval processes have led to situations where more than one developer is given (or believes they have been given) the right to develop the same project site. This resulted in significant confusion and costs to resolve the dispute with the developer eventually exiting the specific market until more certainty and transparency are provided within the project approval process. Among other hurdles, bad policy has contributed to limiting the volume and usefulness of corporate-level investment disbursed to the sector. While energy access minigrid companies have raised over $500 million cumulatively according to Wood Mackenzie data, minigrids still represent only 20 percent of total capital raised in the energy access sector to date. Largely missing is the medium-tenor (ideally concessional) debt that rural infrastructure assets require. The sector has, to date, raised over 70 percent of its capital as strategic equity at the corporate level, which has hampered project economics and has required significant creativity to recycle capital back into the project pipeline. A recent study from Wood Mackenzie evaluated and scored the policy landscape for energy access minigrids globally against a 30-point checklist. Though there are some standouts like Nigeria and the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, the 15 policies evaluated scored a disappointing average weighted total of only 59/100. Wood Mackenzie’s research makes it clear that many policies now in force were written with implicit favorability toward the deployment of public or community-owned systems rather than privately owned and operated ones. Even in the cases where regulations have been implemented with the aim of scaling up private participation, most policies do not sufficiently de-risk the project development cycle and the operational phase of the sites to allow mainstream private capital to be comfortable. While the sector is still too immature to have proven track records of long-term assets in operation or clarity on best practices for policy, we found that currently, the most critical elements of minigrid policies are clear and adaptable licensing processes, transparent and firm measures protecting the rights of developers when the grid arrives, tariff approval processes that allow developers to charge cost-reflective tariffs and the facilitation of fiscal support mechanisms and/or access to finance facilities — at least a few of which have systemic gaps across the global landscape. Unfortunately, these systemic policy gaps are only part of the picture, and therefore, building an ideal minigrid policy based on best practices, even for a single market, is not a very straightforward task. The diversity and relative immaturity of the market highlight the inconsistent views on best practices for bankable minigrid policies between archetypal developers, investors and public bodies such as regulators and state utilities. Simply put, many of these stakeholders often do not agree on what they want out of a minigrid policy, may not know what they want out of a minigrid policy, or may outright oppose a minigrid policy, whether by commission or omission. And depending on governance structures, regulatory bodies or utilities may be constrained in their ability to iterate improvements to policy in alignment with private developers. Our conversations with these private minigrid developers reveal at least high-level consensus on policy design elements, as well as disparities in how their relationships with state-owned utilities are viewed, with some looking to outcompete those entities for customers and quality of service while others present as partners, particularly where regulatory resistance to private minigrids exists. As a result, the question of what constitutes best practice in minigrid policy doesn’t yet have a very straightforward answer. It is worth recognizing some very commendable recent and ongoing efforts to develop template policies and inform regulators with data (such as the State of the Minigrids Market Report, the African Minigrid Developers Association Benchmarking report, the Minigrid Policy Toolkit 2.0, and the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program Minigrid facility report, among others), but we believe the sector is currently constrained by a misalignment of stakeholder incentives. In collaboration with our friends at Cadmus Group, we sought to lay out the overlapping and conflicting incentives for archetypal developers, regulators, policymakers and utilities and offer some guidance on how to get this right by getting everybody on the same page. As with any nascent industry, there are divergent views about the allocation of risk through and the mechanisms for procurement in current regulatory frameworks for minigrids. Most stakeholders generally agree on the need to develop some form of simplified licensing process for minigrids, as well as technical and service standards.

But when it comes to tariffs, grid arrival and fiscal supports, it can often feel like everyone is reading from a different sheet of music. Much of this tension can stem from governments with little fiscal capacity to offer financial support, utilities that are highly sensitive to any impact on their revenue streams, and persistently high costs of doing business in many emerging markets. However, these tensions also represent opportunities for greater collaboration and tradeoffs. For instance, in the case of grid arrival, some developers are wary of stringent interconnection standards as they increase project risk and cost. These developers may be willing to make the investments if policymakers and utilities could offer reasonable compensation. These policy challenges the minigrid sector faces are not new; most new sectors of regulated industries struggle to establish transparent, long-term policy that minimizes soft costs and allows investors to earn their required returns. In its early years, the solar industry faced similar problems and achieved scale and maturity through supportive policy and declining costs. But there are some unique challenges to the minigrid sector that are important considerations in policymaking, including the integration of several technologies including costly batteries that make harmonized tariffs unbankable, significant demand stimulation and demand-side management challenges, and promising but nascent add-on productive use business models. These also are not unsolvable problems, but they do require collaborative and iterative policymaking and a mutual understanding of the interests of each party, which will help establish best practices over time and help move minigrids into the mainstream. *** For more, get Wood Mackenzie's latest report, Evaluating Minigrid Policies for Rural Electrification: Scoring Regulatory Risks as a Precondition to Investment. https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/disconnects-between-minigrid-policy-stakeholders-keep-sector-bankability-at-bay

3 Comments

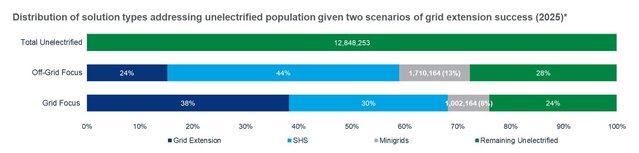

Solar home systems are effective for rural households. But for hundreds of millions, minigrids may be lowest-cost path toward electrification. BENJAMIN ATTIA, CAITLIN CONNELLY, AND ISAAC MAZE-ROTHSTEIN | JUNE 01, 2020 Whether booming off-grid power demand in emerging markets is met with grid extension or distributed renewables will be central to the growth story of the global clean-power sector. As the technological and financial tool kit for providing affordable, reliable, appropriate and clean power to every household and business continues to expand, deployments of off-grid, decentralized, renewable energy systems will take an increasingly larger bite out of present and future power demand on the grid in countries that represent over one-third of the world’s population. On-grid and off-grid power service offerings will increasingly see convergence as next-generation distributed energy service companies continue to evolve and scale. Because the future grid will be increasingly renewable, low-cost, digitally managed and, eventually, demand-following, the diffusion of off-grid systems is still highly interrelated with the rest of the grid. Relatedly, low-energy-access countries’ urgent need for large utility-scale generation and grid infrastructure upgrades cannot be overstated; while solar lanterns and solar home systems (SHS) are an effective and targeted solution for rural households, small-scale distributed solutions cannot power industrialization and economic growth. In recent years, sector stakeholders have increasingly rallied around the flag of integrated electrification planning, which we’ve previously dubbed the “growth game-changer” of the next decade of the decentralized renewables market. Put simply, integrated electrification planning efficiently allocates shares of the remaining addressable market for new electrification connections to different technology solutions (think grid extension projects, standalone solutions like solar home systems and, increasingly, renewable minigrids). These planning exercises are capitalizing on advances in tools including geospatial surveying, new granular demographic data layers, customer surveys, historical electricity consumption data and artificial intelligence to optimize the extension of electricity service to homes and businesses at least cost and with maximum speed. Countries including Togo, Senegal, Nepal and Kenya that have begun implementing integrated electrification plans will minimize connection costs, stranded asset risk and unnecessary competition while maximizing the customer footprint and growing demand with appropriate solutions for each offtaker. Minigrids the lowest-cost option for many Minigrids have an increasingly pivotal — and often underestimated — role to play in the future electricity mix envisioned in integrated planning exercises. Many of these historical analyses skew heavily toward solar home systems over minigrids due to their lower connection costs, but they often overestimate standalone SHS’ ability to meet demand from small and medium-sized enterprises and make broad assumptions about system longevity, replacement and upgrades over time. Lighting Global estimated that 420 millionpeople now use standalone off-grid solar, while the World Bank's Energy Sector Management Assistance Program (ESMAP) estimates that another 47 million people rely on minigrids, a nearly tenfold difference. But the future potential in the minigrids sector is staggering; credible estimates suggest that minigrids will be the least-cost solution for 100 million Africans and up to 292 million peopleglobally by 2030. By the same year, ESMAP estimates that globally, minigrids could carry a USD $3.3 billion annual profit potential for private sector developers. While the long-term trend of corporate-level investment in off-grid solutions is aggressively positive, minigrids have been a categorically underfunded segment of energy access markets, raising only 20 percent of the total corporate-level capital for energy access sector since 2010, according to Wood Mackenzie data. In Wood Mackenzie’s Energy Transition Practice, we’ve been taking a much closer look at minigrid markets as of late, and we recently zoomed in on Kenya as an compelling case study to apply a contextualized market evaluation methodology and draw some lessons for the global minigrids sector. Kenya is neither the largest nor the most robust private-sector minigrid market globally, but a few rarely concurrent attributes about Kenya’s market make it an attractive case: its impressive progress toward universal electricity access on and off the grid, prioritization of comprehensive national electrification strategies, and a mature and well-studied SHS market. Kenya's rapidly rising electrification rateKenya’s electrification rate has risen aggressively from 42 percent in 2015 to 75 percent in 2018 on the back of myriad national electrification programs, as well as it being one of the epicenters of the global solar home system market for many years. The 2018 Kenya National Electrification Strategy set a goal for universal access by 2022, aiming to address 60 percent of the remaining 12.8 million Kenyan residents without electricity with grid extension and intensification and 40 percent with off-grid solutions such as minigrids and SHS. These goals are bolstered by three World Bank-financed programs: the Last Mile Connectivity Program (LMCP), the Kenya Electricity Modernization Program (KEMP), and the Kenya Off-Grid Solar Access Project (K-OSAP), which have collectively attracted $1.3 billion in committed financing to provide electricity access to 1.1 million Kenyans by 2023. But not all is rosy. Despite Kenya Power’s (KPLC) impressive advances in expanding the rate base by connecting over 3.25 million new customers since 2015, largely through the LMCP, most of these new customers have been low-income peri-urban and rural households. These customers consume on average only 8 to13 kilowatt-hours per month and cost significantly more to connect and meter compared to urban customers who consume on average 40 to 50 kWh per month. Additionally, many of the LMCP contractors connected hundreds of thousands of customers without metering them in 2016-2017 before the election, resulting in even less cost recovery from the expensive investments in the distribution network to connect low-demand customers. Consequently, KPLC’s net earnings declined by 92 percent year-over-year in 2019, driven by continually stagnating electricity demand, increases in power purchase and finance costs, and rampant power theft from unmetered customers and cartels that have cost the company a running tab topping KES 20 billion (~$185.5 million). As a result, the future growth of the private minigrid market in Kenya is most sensitive to the success of the national grid extension programs, particularly the LMCP. We’ve therefore modeled both a grid-centric and off-grid centric scenario. We estimate that minigrids will serve between 1 million and 1.7 million Kenyans by 2025, representing between 8 and 13 percent of the remaining residents who do not have electricity. Private-sector players are positioned to serve 55 percent of new connections. Across all technology sets for electrification, we forecast that Kenya will reach 94 percent electrification by 2025, falling short of the 2022 target but continuing its progress toward universal access. Kenya is a strong example of the increasingly convergent worlds of grid-connected and off-grid power markets. As integrated electrification planning becomes a more standard tool for utilities and regulators, the role of minigrids as a key ingredient will become increasingly apparent.

*** Download the free executive summary of Wood Mackenzie's new report, The Missing Piece to the Integrated Electrification Puzzle: A Bottom-Up Study of Kenya’s Energy Access Minigrid Market. https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/minigrids-are-the-missing-piece-of-the-integrated-electrification-puzzle |

GTM ArchiveJust a place to keep the full text of articles published on greentechmedia.com, since the site has unfortunately since been shut down. |